Antonym: irony–armoured edition

6.8 minutes to read. One week to find a way out of the rabbit-holes.

Dear Reader

I read the headline “Bored Ape Twitter Hacked and NFTs Stolen” and moved on. Later, I realised I hadn’t been sure whether the story was a joke or not. I also realised that I didn’t care enough to find out. If it was a joke—it was, apparently, not—what would the point be? To satirise an NFT-hustle scene that seems to be rather good at satirising itself? Or an attention-grabbing display of irony by the story originator?

Irony is now deployed as a kind of social reactive armour or intensely realistic camouflage. Irony-clad thinkers of the American New Right abound in a careful, observational piece by James Pogue for Vanity Fair, “Inside the New Right Where Peter Thiel Is Placing His Biggest Bets”, during a visit to a conservative conference in Florida.

The article references the episode of Succession season three, “Pretenders to The Throne”, in which the Roy family are at a right-wing event picking a new candidate for US President.

“It’s a nice safe space where you don’t have to pretend to like ‘Hamilton.’”, explains Tom Wamsbgams to cousin Greg…

“Well, I like Hamilton,” replies Greg.

“Sure you do. We all do,” deadpans Tom.

That Succession episode delighted many New Right-ers with its dropping of some of their choice-est meme-language including “integralist” and “Medicare for all, abortions for none”. Other exotic neologisms abound: “black-pilled” (coming to believe it’s too late to save the world) and “the cathedral” (the perceived left-wing media-academic complex that sets and guards a liberal consensus).

For many, the polarisation in politics is something to de-escalate, a problem that can be negotiated. The New Right miaspora have taken themselves outside of the the context of contemporary politics. Many are of what you would recognise as the right, while others are harder to pin down—they definitely don’t want to be pinned down. Their views might be the seed of a new political movement, or an aesthetic pose. “Either’s fine”, would be the response to that observation, I imagine.

This weekend’s Lunch With The FT could be thought of as the Cathedral Strikes Back, in New Right lingo. Jonathan Haidt wrote the brilliant—if you haven’t read it stop now and go and get a copy—The Righteous Mind in 2012 (one of my favourite non-fiction books I read last year). The interview, by Jemima Kelly, also serves as a handy TL;DR for Haidt’s recent essay “Why The Past 10 Years of American Life Has Been Uniquely Stupid” (an estimated 30 minute read, and well worth it).

The root of discourse unravelling due first to polarisation and then irony is social media, says Haidt. After 2014, the share and the like buttons’ created a massively. multiplayer social game where the points were awarded for attack, high emotion and outrage:

This new game encouraged dishonesty and mob dynamics: Users were guided not just by their true preferences but by their past experiences of reward and punishment, and their prediction of how others would react to each new action.

In the FT interview, Haidt suggests some ways of reining it all back in:

But there are simpler, non-governmental interventions that could help too. “If everybody would just cut their social media use by 50 per cent, they would generally be happier and our problem would be ameliorated because the whole thing is built on us contributing content.

I agree with the caveat that blogs and email newsletters don’t count in that category. Both are longer form and encourage us to slow down in the creation consumption and sharing of ideas and opinions.

X2 = X10: the formula that built ad empires

When I was young executive in the comms industry I wanted to understand more about how and why agencies bought other agencies. I’d read that mergers rarely added value to either company, so why did they still go after this policy rather than organic growth? Someone whose job it was to go and buy agencies to “roll up” into a group kindly sat me down and drew it out for me.

It was a simple, yet confusing formula. Over the years I’ve thought maybe I mis-remembered how strange the explanation was—they seemed to be saying that the 2+2 =5. Well actually, 2+2=10. And then I read the same formula in a Times article about Sir Martin Sorrell’s S4 Capital:

[at WPP] Sorrell would buy a company for a price based on two or three times its annual sales and investors in S4 would value them at ten times sales via the share price. “It didn’t seem like a house of cards, but the valuation was a house of cards,” O’Shea said.

And yet, one might say, there is WPP: still a large company, with real profits and real growth.

Well, perhaps not quite. Simon Martin, founder and CEO of in-housing agency Oliver, pointed out that before the pandemic the big ad agency groups were shrinking in real terms because growth lagged behind inflation.

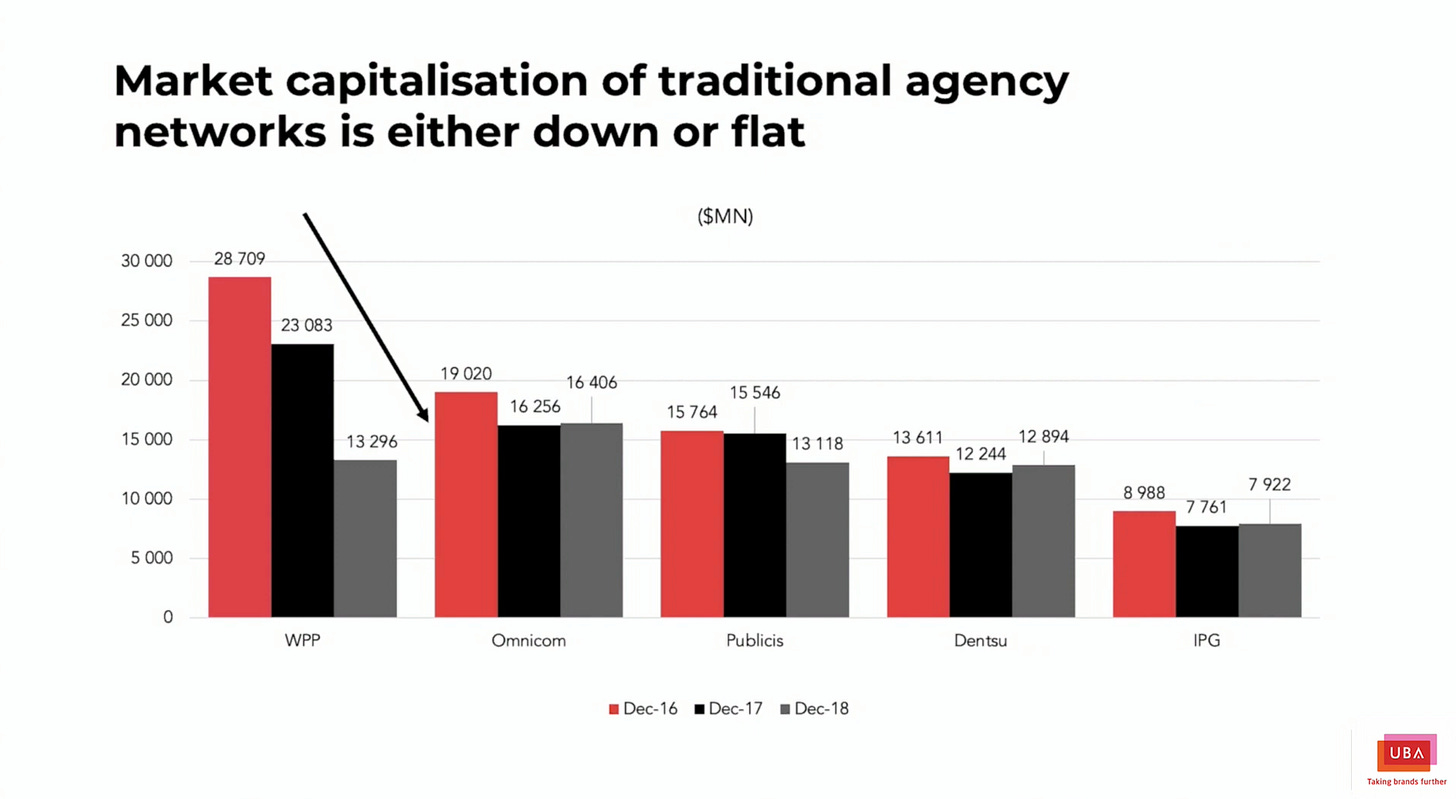

The headlines now are about “record organic growth”, but this is mainly bouncing back from the lows of the pandemic, and market capitalisations are about where they were mid-way through their decline in 2018.

The sums made sense at WPP and S4 Capital while the growth continued and the markets rose:

By September last year, S4 was valued at £4.5 billion. It was a staggering achievement for a business launched just a few years earlier and especially for one with underlying profits of about £60 million. The comeback was complete — or so it seemed.

But then the bubble burst. The company warned margins were falling, which it said was due to hiring staff. Then a tech sell-off gripped markets as interest rates began to rise, sweeping S4 along with it. After last week’s lurch further south, the company is now valued at £1.8 billion.

But markets have stopped rising now and disruptions are happening everywhere. And all sorts of business models, from Bulb to streaming video don’t make sense in quite the same way anymore. Like Bulb, many in fast-growing groups like S4 Capital are incentivised by share options. They don’t have the earn-outs that were and are standard practice in marketing services M&A, but they do have senior management teams and talent holding shares that are worth a lot less now.

More DALL-E 2 offerings

I mentioned the insanely clever DALL-E 2 AI image generator last week. While I’m still waiting for access (it may never come) here’s a subreddit where people with DALL-E 2 access are posting images based on suggestions of prompts – examples below:

“A detailed photograph of a piglet wearing a small fedora, studio lighting:”

A detailed neoclassicism painting depicting the frustration of being put on hold during a phone call

DALL-E 2 and its underpinning technology, GPT-3 from OpenAI, get their inputs from the web. I took the image from the top of this newsletter and fed it into Google Image search – you plainly can see where DALL-E 2 gets its inspiration:

Genius steals, and so does AI.

Words, pictures and data from the FT

The graphics–and–copy blend of article format has been evolving nicely. The FT’s Big Read feature this weekend is about the food security implications of the Russia-Ukraine war. A series of photos is used to establish the piece, grounding it in the working day of a farmer, before returning to the text and then using sets of graphics that move as you scroll to illustrate the story. It works very well, enhancing the story and deepening understanding rather than distracting. I found it worked much better on an iPad screen than a laptop if you’re going to take a look.

If you don’t have a subscription or the will to navigate the subscriber log-in, here’s a short video of the scrolling experience:

Books

How To Be Animal, by Melanie Challenger

A killer opening three sentences, that wins the reader’s confidence, curiosity and sets a mighty intent for how the book will progress:

The world is now dominated by an animal that doesn’t think it’s an animal. And the future is being imagined by an animal that doesn’t want to be an animal. This matters.

Designing Organisations, by Naomi Stanford

Principle 2: Organisation design requires systems thinking: about the many elements of the organisation and the connections between them

Designing the elements such that they interact seamlessly requires “systems thinking”, defined as “a set of synergistic analytic skills used to improve the capability of identifying and understanding the organisational elements and their interdependencies, predict their behaviours and devise modifications to them in order to produce desired effects”.7 The value of systems thinking is that it “encourages the designer to question the existing system – the boundaries, perspectives and relationships that could be relevant to addressing a complex issue. Through systems thinking, designers can generate deeper insights, guard against unintended consequences and co-ordinate action more effectively.

Watching

Boyz-N-The-Hood. Still got it. Cuba Gooding Jr.’s outfits are the only thing that date it.

Boiling Point (Netflix). Full disclosure: this film is so stressful I’m hoping to finish it on the second attempt. Stephen Graham is like an anxiety chain reaction contained in a boxer’s body. Utterly amazing.

Slow Horses (Apple+). Reliable spy fun. It’s not Le Carré—but then again, what is?

The Shining Girls. Apple+ does it again. Elizabeth Moss and a time-slipping serial killer plot perfectly executed (pun unintended but allowed to remain).

Final quote

...every generation has to rethink what it means to be literate in their own times.

— The Golden Thread, by Ewan Clayton

Thanks for reading. I hope you found something you might otherwise have missed.

Antony