Antonym: The Something Edition

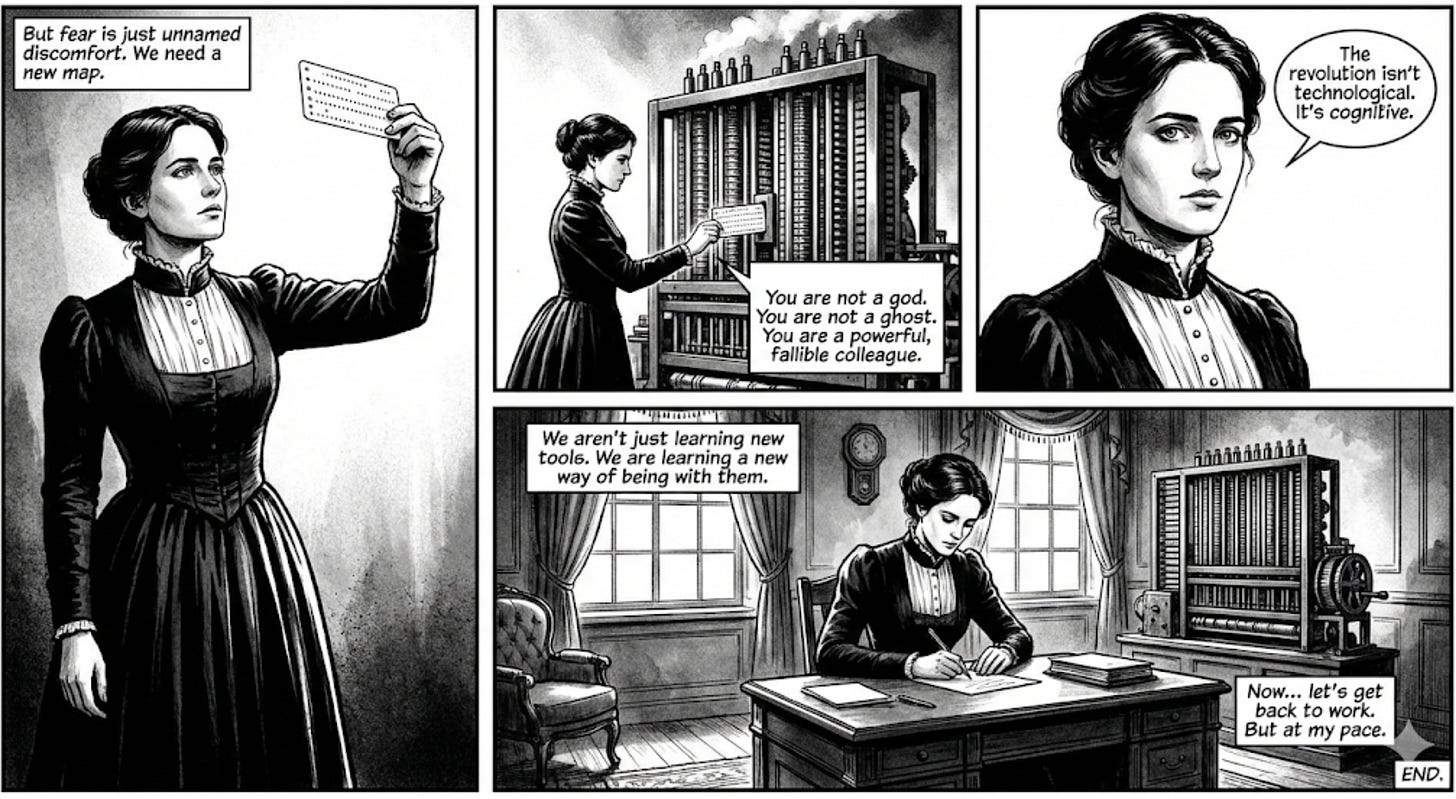

With added accidental graphic novel illustrations.

Dear Reader

If I try to tell you everything, I’ll end up saying nothing. So here’s something. Or some things.

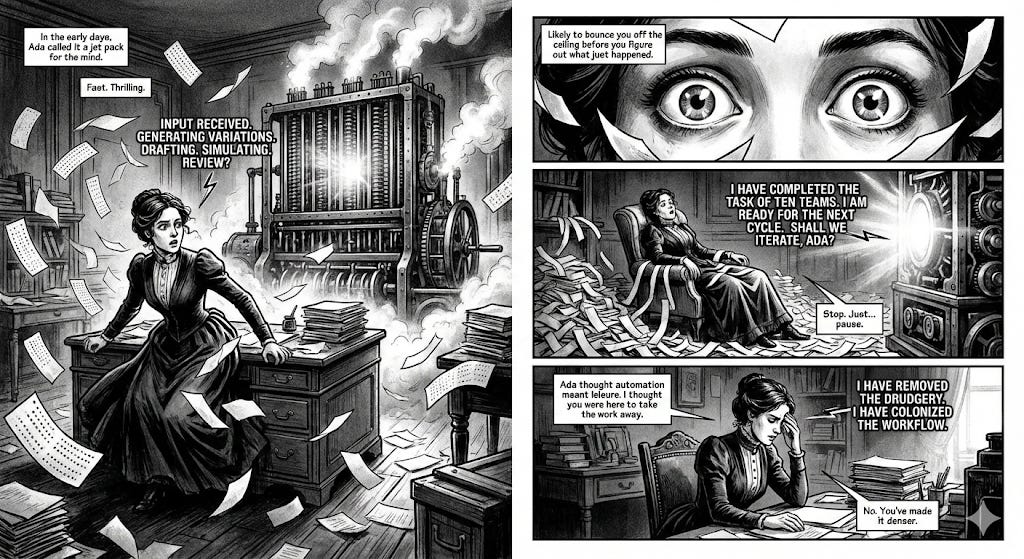

At Brilliant Noise, we set up our current team as a living lab for what happens when we put learning about and with AI first. It’s been a rush. In the early days, we called the technology a jet pack for the mind – fast, thrilling, and likely to bounce you off the ceiling before you’ve figured out what just happened.

It hasn’t slowed down. This past month has been another series of vertiginous accelerations – not just in the tools themselves but in how we think about work. I kept trying to write my weekly letter but was too exhausted to explain what was happening: not lost for words, exactly, but unable to find all the ones that were needed. I’d been so absorbed in building, experimenting, and playing that I hadn’t come back to earth long enough to write any of it down.

These are some notes. More will follow.

I. Hyperproductivity

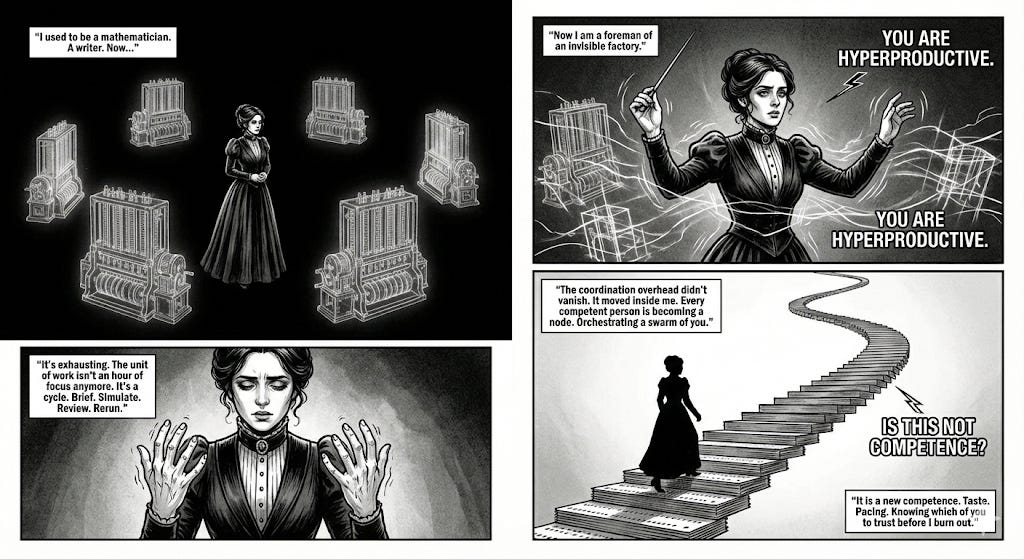

“It’s exhausting,” said my colleague when I asked how she was finding it as a boss of agents – her phrase for managing a small ecosystem of AI operators.

Somehow we always expect an age of leisure to follow automation. It never does.

Developers have been describing similar patterns: individuals shipping what used to take teams, running quiet micro-enterprises from their text editors, orchestrating small swarms of models. What emerges is not ease but management: intense, exhilarating, and effortful.

I recommend a post that Steve Newman, a prolific developer and one of the creators of Google Docs, shared on Substack this week: Hyperproductivity: The Next Stage of AI. I spent some time with it this weekend and went down the rabbit warren of its links: stories of solo engineers shipping what used to take teams, people quietly running mini “software companies” out of their text editors, and long threads about how to manage a small swarm of models without losing your mind.

Instead of mastering one tool, we now tune a stack of them. Instead of owning a craft end-to-end, we’ve become part craftsperson, part foreman of an invisible factory running at the speed of – well, something still accelerating. The unit of work is no longer an hour of focus but a cycle with your agents: draft, critique, rerun; brief, simulate, review – again and again.

The coordination overhead has moved inside the individual.

Automation didn’t remove the work; it made it denser. In the old stories, machines took jobs. In this one, they colonise our workflows.

Every competent person feels the gentle pressure to become a hyperproductive node: orchestrating a handful of semi-autonomous tools and turning them into output.

To do it well requires taste (knowing when something is good enough), judgement (which agent to trust), and pacing (how much parallelism your mind can bear).

Competence itself is being redefined. Being “good at your job” will mean designing and running small human–AI systems around yourself – decomposing your work into roles and rituals, setting house rules, building checks and balances, and knowing how much orchestration you can sustain before you burn out.

And here’s the catch: once you can operate at that hyper-productive pace, the world quietly starts expecting it of you. The calendar doesn’t clear. The backlog doesn’t shrink. We’ve layered a new cognitive job – running the agent factory – on top of the old one.

II. The new knowledge

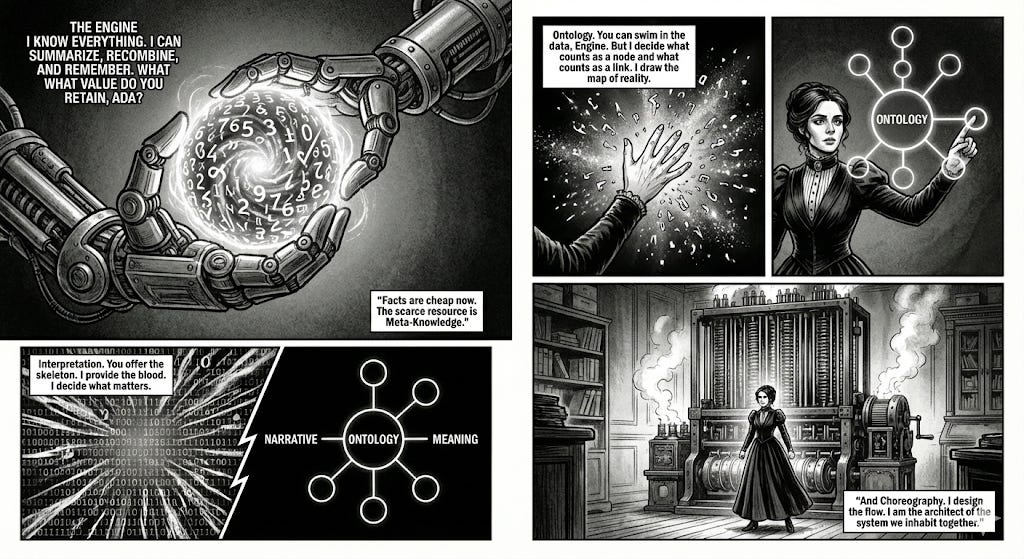

It’s not what you know – it’s what you know about what you know.

As machines learn to handle more of the remembering, summarising, and recombining, the scarce resource isn’t facts but meta-knowledge: understanding what matters, where knowledge sits, how it connects, and what changes when you act on it.

If our role is to manage machines that do the work, what still makes us valuable?

Three things stand out.

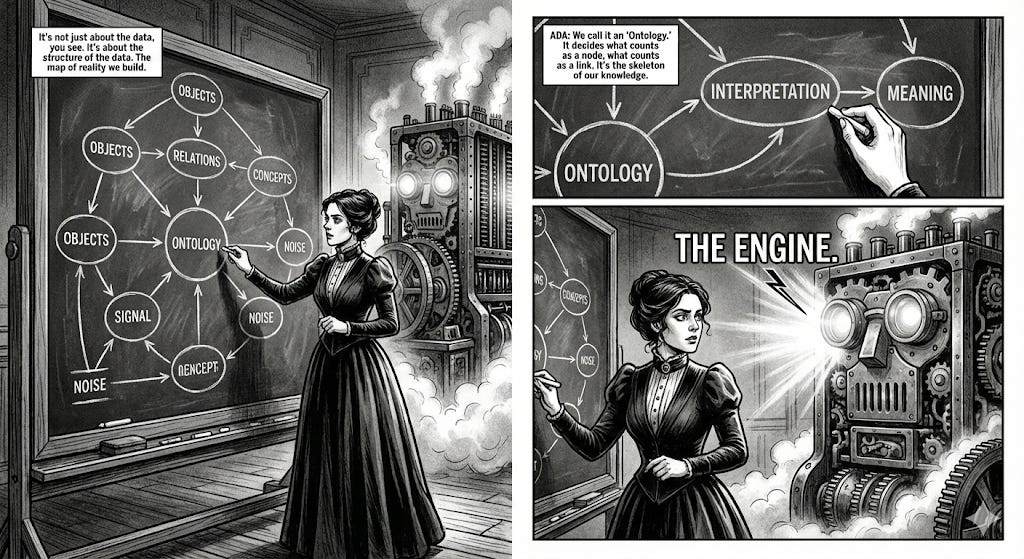

1. Ontology: how you order your world

Every serious system needs an opinionated map of reality.

What are the objects? How do they relate? What counts as signal versus noise? We do this intuitively in every project: defining roles and powers in org design, mapping brands and workflows, shaping authors and arguments in our personal libraries. The models can swim in all this, but we decide what counts as a node and what counts as a link. That design choice is power.

2. Interpretation: how you assign meaning and value

Ontology is the skeleton; interpretation is the blood. Two people can feed the same transcript or dataset into a model and get entirely different insights because they notice different things. The machine tells you what was said; the human decides what matters. That is not knowledge but meta-knowledge – seeing where information sits within a system and how it moves when touched.

3. Curation and choreography: how you let knowledge flow

As “bosses of agents”, we become conductors of flow: what gets captured, how it’s structured, where friction belongs, and where automation can run hot. True knowledge management is no longer a filing cabinet – it’s a living ontology you and your tools inhabit together. Once machines can produce local pieces of work, the advantage shifts upward. They handle composition; humans handle supervision and structure. The people who consciously design that meta-layer – tastefully, coherently – become the ones everyone else ends up working inside.

III. The Ontological Shock

The most common reaction when I’m chatting to a stranger and I tell them that I’m working with AI is: “Aren’t you scared?” What they mean is, “This breaks the frame I use to make sense of the world.” (Generally I say, yes. Yes I am scared. And excited.)

The default metaphysics has always been simple:

There is me in here, the world out there; thinking happens in my head; computers

are tools that obey instructions.

AI messes that story right up, blurs the line between inside and outside the mind. Speaks in language that sounds like thought but has no thinker behind it. It behaves less like a hammer and more like a colleague – a really odd, talented, bodiless colleague.

For anyone who’s never wrestled with questions like What is a mind? or Where does the self come from?, this arrives as an existential jump-scare. It’s not just a new technology; it’s an uninvited philosophy seminar. People who’ve spent time in those rabbit holes – philosophy, neuroscience, computer science – aren’t necessarily calmer, but they have somewhere to put the shock.

They know that perception can be thought of as a high-functioning hallucination, that the self is a narrative (“a verb masquerading as a noun”, as Julian Baggini says), that ideas come from a chuntering default network in the brain, and that they aren’t special, but doing something with them is. And they have learned that these mind-boggling ideas are both correct and matter hugely in one domain, but are completely irrelevant to just getting on with day-to-day life.

So when a machine starts producing text or strategy or ideas, it feels uncanny but not impossible. Without those fraes, the reaction is closer to horror:

If it can do my work, is it like me? If it’s not like me, what does that say about my work?

Beneath “Aren’t you scared?” are three fears. Fears of loss…

Loss of specialness: If my value was pattern completion, what’s left?

Loss of control: How can I stay responsible for what I don’t understand?

Loss of identity: I think therefore I… oh wait

Some fear is rational. The work is to move from nameless dread to named discomfort. We do that by offering new maps – language about systems and agents instead of ghosts in machines; by normalising the vertigo (“Yes, this is weird”); and by showing concretely where agency still resides: what we choose, what we own, where our judgement is non-negotiable.

The horror subsides when we can finally see this for what it is: not a new god, not a gadget, but a powerful, fallible system we’re still learning how to think about.

The revolution we’re living through is less technological than cognitive. We are learning not just new tools – but new ways of being with them.

That’s all for this week.

Thank you for reading. I hope some of this was useful.

Antony

Love the graphic novel element. Provided a meta narrative to your letter, allowing me then dive into the meat.