This is an longer article to go with this week’s usual Antonym Edition.

We can’t control systems or figure them out. But we can dance with them! — Donella Meadows, pioneering systems thinker.

Currently, many of us are playing and sharing recipes for things you can make with AI tools (although you have to put on a serious face and call the play experimentation and the recipes have to be called “prompt engineering” in a voice two octaves lower than you usually speak in).

I’ve been doing this and sharing some here, like making a ordered shopping list or whole presentations and writing up meeting notes.

This week I had an experience that made those feel like basic moves, that suddenly I’d learned to dance in a new way. It started with a simple experiment and then spiralled into an adventure with ideas. Once it was happening, I almost couldn’t stop – a sensation like in a dream when you start to fly, or realise you are piloting some strange and wonderful vehicle.

The following isn’t a recipe, but it does include some of the steps I took, and some of them may be useful to you. I was using ChatGPT for the most part. If you would rather not pay the extra $20 to use this, you may get similar – or “good enough – results with the free standard ChatGPT or its rival Anthropic’s Claude. Apps such as Poe will let you have a few free goes on both platforms. But the tech isn’t the point here; the way of thinking and the possibilities and how it feels are what I want to share.

Accelerated inspiration

It started something that sparked some curiosity. My wife, whose passion is garden design, was talking about a famous designer called Piet Oudolf. He creates gardens that are self-sustaining, support wildlife and other wonderful things. The one I knew was the High Line garden in New York, a long, narrow strip of a park made on an old elevated subway track in the Meatpacking District.

The High Line, New York City (20th Street, looking downtown). Credit: (cc) Beyond My Ken.

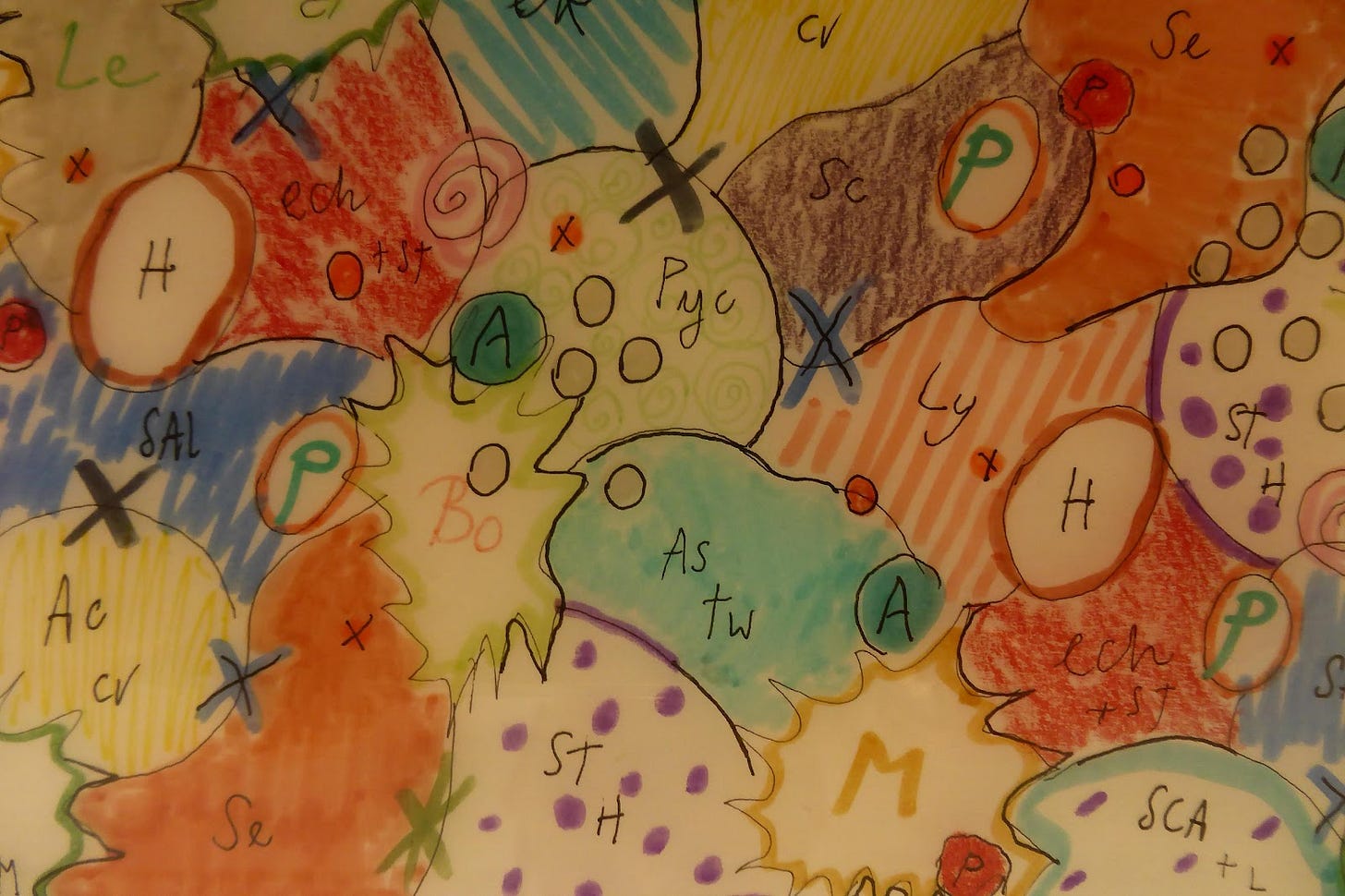

His planting schemes often look like wild prairies but are meticulously planned systems of systems. The drawings, she said, look unlike any other type of garden design, more like scientific diagrams of mitochondria than planting plans. Here’s an example:

And here’s some detail from a design which expresses the way that different groups of plants interact with each other over the seasons.

Image: Segment of planting design for Hauser & Wirth Somerset garden Credit: (cc) John Lord

The description made me think about systems thinking of course; Oudolf seems like a systems thinker – focused on connections and how different elements interact with each other.

Exploring a connection

I asked the latest version of ChatGPT (currently premium, running GPT-4) this: “Can you show me some images of Piet Oudolf’s designs and tell me about his design philosophy?”. It returned the following, a useful primer on his approach which tallied with and built on what I knew already:

Piet Oudolf is a Dutch garden designer, plantsman, and writer who is renowned for his innovative approach to planting design. He has been a leading figure in the New Perennial Movement, a gardening style that emphasises the use of perennial plants, particularly grasses, and focuses on creating naturalistic landscapes. His approach to garden design is characterised by several key principles:

- Plant-driven design: Oudolf places a strong emphasis on selecting plants for their aesthetic qualities, such as form, texture, and colour, rather than focusing solely on their horticultural characteristics. This plant-driven approach results in gardens that are visually engaging and have a naturalistic feel.

- Seasonal interest: Oudolf's designs prioritise plants that provide interest throughout the year, not just during the peak of the growing season. He selects plants that have beautiful seed heads, attractive winter silhouettes, or striking fall colour, ensuring that the garden remains engaging even during the colder months.

- Layering: Oudolf's gardens are characterised by a layered planting approach, in which plants are arranged in a way that mimics the structure of natural ecosystems. This results in gardens with a diverse range of plant heights, densities, and textures, creating a sense of depth and complexity.

- Ecological considerations: In his designs, Oudolf often incorporates native plants and emphasises the importance of supporting local ecosystems and wildlife. He believes that a garden should not only be aesthetically pleasing but also contribute to environmental conservation and biodiversity.

- Embracing imperfection: Oudolf's gardens are not meticulously manicured spaces, but rather, they embrace the natural processes of growth, decay, and regeneration. This results in landscapes that have an organic, evolving character, which reflects the inherent beauty of nature.

Some of Oudolf's most famous projects include the High Line in New York City, the Lurie Garden in Chicago, and the Millennium Garden at Pensthorpe Natural Park in the UK. His work has had a profound impact on contemporary garden design, inspiring countless designers and gardeners to embrace a more naturalistic and ecological approach to landscaping

Amazing. Was there much writing about the connections with systems thinking in his approach? ChatGPT said no, but that it did see parallels:

While there isn't a direct and widely-discussed connection between systems thinking and Piet Oudolf's work in garden design, one can still draw some parallels between the two. Systems thinking is an approach to problem-solving that focuses on understanding the interrelationships and interdependencies within a system, rather than just focusing on individual components in isolation. It seeks to understand how elements within a system work together and how changes in one part of the system might affect other parts.

In the context of Piet Oudolf's work, one could argue that his approach to garden design embodies some principles of systems thinking, such as:

- Emphasis on relationships: Oudolf's designs prioritise the relationships between plants, considering how they work together in terms of form, texture, colour, and seasonal interest. By focusing on these relationships, he creates gardens that have a more cohesive and naturalistic appearance.

- Holistic approach: Oudolf considers the garden as a whole, rather than just focusing on individual plants or elements. His designs take into account the overall structure, composition, and aesthetic qualities of the space, as well as its ecological impact and support for local wildlife.

- Adaptation and change: Oudolf's gardens embrace the natural processes of growth, decay, and regeneration, allowing the landscape to evolve and change over time. This approach is consistent with systems thinking's emphasis on understanding the dynamic nature of systems and their ability to adapt to changing conditions.

- Ecological considerations: Oudolf's emphasis on native plants and supporting local ecosystems is in line with systems thinking's focus on understanding the broader context in which a system operates, as well as its connections with other systems. By considering the ecological impact of his designs, Oudolf contributes to the overall health and sustainability of the environment.

While these parallels can be drawn, it is important to note that the connection between systems thinking and Piet Oudolf's work in garden design is not explicit or widely recognised. However, it can be interesting to consider how his approach to design might resonate with the principles of systems thinking and contribute to a more holistic and interconnected understanding of garden design and landscape architecture

Amazement aside, what was going on here? This was better than search engines. Not just the creaky SEO-muddied search results you get from searching for anything, but something going beyond what was there and finding synthesis, connections between fields. I was learning about Oudolf and being reminded of key elements of systems thinking. It was the kind of short article or blog post I would write over a couple of hours, once I’d been able to read enough about Oudolf and consult my notes on systems thinking concepts. Instead, it was right here in front of me. This is – or something similar – is what I would have written.

Combinations a go-go

I felt slightly giddy.

What did I want to do now? Turn those notes into an article? Or go further?

Oh, further – of course, go further. Where I was headed was how I might apply some of this as metaphor or inspiration for my own work. What would Oudolf’s approach and lessons from design thinking apply for, say something like designing an organisation, the way that teams or departments fit together. This was something I had found hard in the past and suspected there could be better ways of thinking about it. One stumbling block is that organisation design is not an org chart; but, org charts are useful for some things, and expected by people. As soon as you produce a chart, that’s what humans’ territory and hierarchy-attuned minds go to, and it’s hard to get everyone thinking about other aspects, like how the bits work together.

So, I asked:

Piet Oudolf’s designs are famous for how they express his ideas in diagrammatic form. What might an organisation design visualisation look like if you took that approach – describe the images and components and then again as prompts to create those that could be used with DALL-E 2 or Midjourney to create useful elements and diagrams.

And got another analysis with about eight bulleted paragraphs explaining connections such as:

Emphasis on relationships and interconnectedness: Just like Oudolf's approach to garden design, organisational design should focus on fostering strong relationships and understanding the interconnectedness of various departments and roles. Designing an organisation with a focus on collaboration and communication can create a more cohesive and efficient system.

Here’s the full response:

Drawing inspiration from systems thinking and Piet Oudolf's work in garden design can lead to several ideas and principles that might be applicable to organisation design. Here are some concepts that could potentially contribute to better ways of designing organisations:

- Emphasis on relationships and interconnectedness: Just like Oudolf's approach to garden design, organisational design should focus on fostering strong relationships and understanding the interconnectedness of various departments and roles. Designing an organisation with a focus on collaboration and communication can create a more cohesive and efficient system.

- Holistic approach: In line with systems thinking, organisation design should take a holistic view, considering the organisation as a whole rather than focusing solely on individual components or departments. This includes evaluating the organisation's culture, values, and objectives, and aligning them to create a unified and purpose-driven entity.

- Adaptability and flexibility: Organisations, like gardens, need to be adaptable and flexible to thrive in a constantly changing environment. Organisational design should incorporate structures and processes that allow for adaptation and responsiveness to external and internal changes, facilitating innovation and continuous improvement.

- Diversity and layering: Similar to Oudolf's layered planting approach, organisations can benefit from a diverse workforce with a range of skills, experiences, and perspectives. This diversity can foster creativity, innovation, and resilience, and contribute to the overall success and sustainability of the organisation.

- Ecological considerations and sustainability: organisations should consider the broader context in which they operate, including their social and environmental impacts. Designing organisations with a focus on sustainability, ethical practices, and social responsibility can contribute to a healthier and more resilient system.

- Embracing imperfection and learning from failures: Like Oudolf's gardens, organisations should recognise that imperfection is an inherent part of growth and progress. By fostering a culture that embraces experimentation and learns from failures, organisations can continually evolve and improve.

- Balancing autonomy and interdependence: In a well-designed garden, plants thrive both independently and as part of a larger ecosystem. Similarly, organisations should strike a balance between providing employees with autonomy and fostering a sense of interdependence, encouraging individuals to contribute to the organisations overall success.

By applying these principles and ideas, organisations can draw inspiration from systems thinking and Piet Oudolf's work in garden design, potentially leading to more effective, resilient, and sustainable organisational structures.

Now show us what it looks like

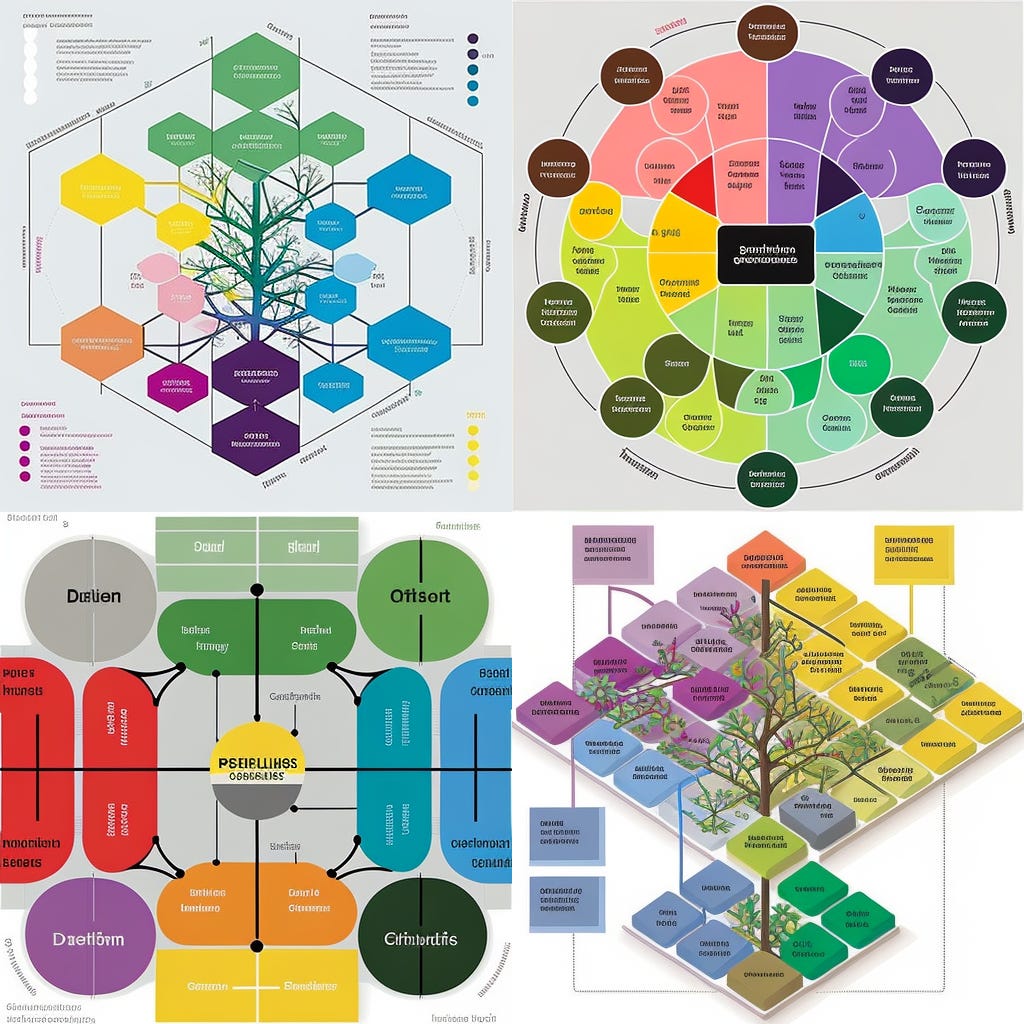

Then there were the prompts. I tried this one in the DALL-E 2 and Midjourney image generators. DALL-E 2 was disappointing. Midjourney gave a credible and interesting set:

I added an instruction to make them appear hand-drawn, like Oudolf’s:

Exactly what I was imagining. Better, maybe.

So, in about half an hour I’d learned huge amounts, explored an untapped area of adjacent innovation in organisation design and mocked up how we might re-imagine org charts.

I was over-stimulated. Excited by the experience. All the dopamine and other hormones fired by my brain sensing new knowledge had me feeling almost dizzy. I had to slow down.

What does this experience tell us about how we can work with AI?

What does this experience tell us about how we can work with AI?

Far more exciting than having AI create content is trying out ideas. When my colleagues in graphic design or creative use image generation AI tool often it if for the mood boards and rough creative territories that would have taken hours or days to produce as part of the process in the past. Writers and knowledge workers can do the same, but aren’t necessarily used to working with multiple possible versions of the same work that are very different from one another.

AI can be a smart study partner or tutor. This was a learning experience as much as a writing or research process. Taking existing knowledge into an adjacent domain is always exciting, what made this different was how fast you could get from question, to idea, to concept to exploration.

The better your questions, the further you go. The chat is more than a simulation, it is a conversation with texts and networks of knowledge. Domain knowledge and curiosity can take you in to other fields fast.

Search engines are so screwed once this catches on. This was a specialised, nerdy, almost academic enquiry, but once you experienced the efficiency and felt the potential of thinking like this, each time I turn to a traditional search engine it feels very limited. Bing has some of this quality, not least because it uses OpenAI’s software. Google could transform this approach.

Reasonably priced, for now. Short-term, the $20 a month for ChatGPT premium seems like a bargain for someone who will use it in their work. Other tools like Claude from Anthropic are similar, and the note-taking app Notion blends Claude and ChatGPT, I believe.

Try it yourself

The following would be my advice to a colleague or friend who is a knowledge worker or creative and is comfortable, but not expert with using search engines and standard productivity tools (Microsoft Office, Google Worksuite or equivalent).

Invest $20 a month and an hour a day to learn to dance with AI. I recommend a month at least with ChatGPT, Notion, or Claude (all of which charge a similar amount) and using it on at least one task where you have a little time to experiment. I’ve found it saves more time than it takes to learn on things like planning, analysis and admin (meeting notes, preparing structures and guides for writing anything from business documents to copy), but this may not be the case for everyone.

Keep notes. Take screen grabs and write a little journal of what you notice, what works and what doesn’t. These may be useful to review later on, but even if you don’t, it will make sure you reflect, if only briefly in the moment, on what is happening.

Be disciplined about process. This is a topic for another article, but being clear about the steps you will take to create something, even designing a big meeting, or sending a concise analysis of a topic, and creating a check-list for the job will help you see where it will be worth trying working with a generative AI tool.

Double check outputs for facts and accuracy. GPT-4 and equivalent generative AIs are more accurate, but still liable to make things up – this includes checking links are real and references to articles or other sources actually exist and say what it claims they do.

Find your rhythm, make your own moves. Every breathless claim of a prompt or tool that can save HOURS or make $ – there are so many on social media currently – should be treated with extreme caution. What worked for one person may not replicate for you. Even scientists find it hard to replicate results in some controlled experiments. Instead of looking for magic spells or artefacts, use the metaphor of dance to learn how to give and take with the tools, find what’s possible and what suits your mind. As well as the unpredictable nature of AI sometimes, the different demands of our specific work and our individual brains are all going to require different techniques and use of tools.

In the spirit of that last point, let’s end with a fuller version of the Donella Meadows quote we started with:

We can’t control systems or figure them out. But we can dance with them!

I [...] learned about dancing with great powers from whitewater kayaking, from gardening, from playing music, from skiing. All those endeavours require one to stay wide awake, pay close attention, participate flat out, and respond to feedback. It had never occurred to me that those same requirements might apply to intellectual work, to management, to government, to getting along with people.

Let’s dance.